- Published on

From Wind Tunnels to Checkered Flags – A Technical Odyssey

- Authors

- Name

- Manoj Gowda

- @nemesis_manoj

Introduction

- I had to write a report and present it at a seminar for a class in my 5th semester in college. I have done my best to give a summarized version of the report below but if you want to dig deeper you can read it here AERODYNAMICS OF F1 RACING CAR.

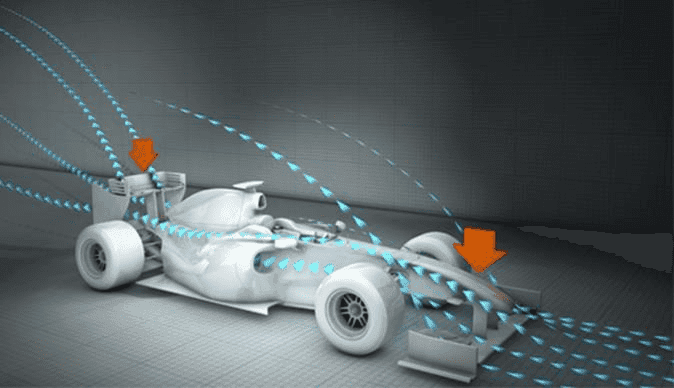

Weighing just 605 kilograms in race trim, propelled by an engine that delivers in excess of 800 horsepower, a Formula 1 car is regularly subjected to braking and cornering forces in excess of 5g. The maximum speed depends on aerodynamic setup, which changes from circuit to circuit, but is usually around 340 kph. At that speed, the geometry of the car produces downforce of around two tons, This invisible force pushes the car into the ground, increasing traction and allowing the car to maintain higher cornering speeds and generate greater braking force.

Since both lift (in this case negative lift) and drag are functions of velocity squared, the ability to deliver an efficient aerodynamic package on race day is a critical ingredient in reducing individual lap times by the fractions of a second that combined are the difference between winning and losing the race.

With engine development now frozen and only one tire manufacturer supplying the whole grid, the aerodynamic package has become a single most important component of race car performance.

Historical Performance Data

| Year | Weight (kg) | Power (bhp) | Downforce (points) | Drag (points) | Time Delta (sec) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 605 | 750 | 300 | 85 | +4.0 |

| 2009 | 734 | 1000 | 360 | 90 | -4.7 |

The development of a car’s aerodynamic package typically relies on an extensive wind tunnel program, conducted in parallel with, and to some extent driven by, an even more extensive Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) program.

What is Aerodynamics

Aerodynamics is the branch of Dynamics that deals with the motion of air and other gaseous fluids and with the forces acting on bodies in motion relative to such fluids.

In the term AERODYNAMICS, AERO stands for air, DYNAMICS denotes motion. Aerodynamics is an engineering science concerned with the interaction between bodies and atmosphere.

Aerodynamic Functions

The aerodynamics of the race car is multi-functional:

- To make it as streamlined as possible.

- To provide downforce for the race vehicle.

- To control the airflow over the car’s body.

The aerodynamics of F1 cars are intensively researched, and annual 5% - 10% downforce increases have been possible if rules don’t change too much between seasons.

All the teams make a large investment in aerodynamic competence as the car with the best aerodynamic package generally wins the championship.

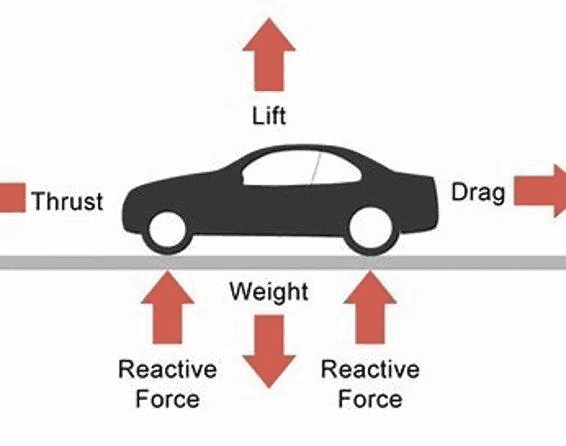

Forces Acting on F1 Car

Thrust

When a body is in motion, a drag force is created, which opposes the motion of the object. So, thrust can be the force produced in the opposite direction to drag, which is higher than that of drag, so that the body can move through the fluid.

One of the largest forces that act on an F1 race car is its thrust - the driving force supplied by the engines, through the wheels, that causes it to move forward (acceleration). In an F1 race car, this force is often several-fold greater than regular cars, although the total weight is much lower than a road car.

Lift

One of the most widely used applications of Bernoulli's principle is in the airplane wing. Wings are shaped so that the top side of the wing is curved while the bottom side is relatively flat.

In motion, the front edge of the wing hits the air, and some of the air moves downward below the wing, while some moves upward over the top. Since the top of the wing is curved, the air above the wing must move up and down to follow the curve around the wing and stay attached to it (Coanda effect), while the air below the wing moves very little.

Downforce

Typically, the term "lift" is used when talking about any kind of aerodynamically induced force acting on a surface. This is then given an indicator, either "positive lift" (up) or "negative lift" (down) as to its direction.

In aerodynamics of ground racing (cars, bikes, etc.), the term "lift" is generally avoided as its meaning is almost always implied as positive, i.e., lifting the vehicle off the track. The term "downforce," therefore, should always be implied as negative force, i.e., pushing the vehicle to the road.

If you can use the shape of the car to generate some downward pressure (usually called downforce) onto the tires, then the car will go faster around the corners. Research into aerodynamics has allowed cornering speeds in “high-speed” corners to be much higher than that which is possible without the use of aerodynamic aids, although it has reduced ultimate top speeds. Track lap times have improved significantly.

- Front Wing

The front wing of a Formula One car creates about 25% of the total car's downforce. Although this only occurs in ideal circumstances. When a preceding car runs less than 20m in front, the total downforce generated by the front wing may become as little as 30% of its normal downforce.

Mainplane running almost the whole width of the car suspended from the nose. Onto the mainplane are fitted two aerofoil flaps, one on each side, which are the adjustable parts of the wing.

A regular front aerofoil is made as a main plane running the whole width of the car (almost at least, limited by FIA regulations) suspended from the nose. Onto this are fitted one or more flaps, which are the adjustable parts of the wing.

On each end of the mainplane, there are endplates. These make sure the airflow passes above and beneath the wing rather than around it. In recent years, these endplates have played a crucial role in influencing the airflow around the front tires, especially after the rule changes at the beginning of 1998 (wheelbase made smaller from 220cm to 200cm).

- Rear Wing

Typically, the rear wing generates 40% of the car's downforce. Like the front wing, its efficiency decreases when another car is close behind.

In 2003, rules have been introduced to try and cut downforce, and therefore grip. An increase in the neutral section has been imposed and the profiles of the flaps and endplates have been altered.

The profile of the rear wing can be changed significantly during a race. A typical change is 4.5 degrees angle on the mainplane and two degrees on the flap.

Adjusting the balance of front and rear wing can help in controlling the understeer and oversteer characteristics of the car. Generally, if you have a lot of understeer, you should increase the front wing angle or decrease the rear wing angle. If you have oversteer, do the opposite.

A diffuser, a common feature in Formula 1, generates downforce at the rear of the racing vehicle. It leverages the Bernoulli equation, akin to a venturi tube, to increase airflow velocity and decrease pressure beneath the car. Unlike wings that push air upwards, a diffuser sucks air under the car, gradually expanding its volume towards the rear. This drop in pressure causes the car to be pulled closer to the ground, enhancing stability at high speeds. To ensure safety, regulations prohibit sharp car bottoms, relying on the diffuser's low-pressure area to create downforce. The diffuser, located under the rear wing, features multiple tunnels and splitters that carefully control airflow to maximize its suction effect.

The design of the car's bottom and diffuser is critical, impacting cornering behavior. Designers must ensure consistent performance under varying conditions and ground clearances. Losing diffuser-generated downforce when riding over curbs can lead to erratic car behavior. Recent advancements in diffuser design, with intricate shapes and sometimes gurney flaps, have made track-specific adjustments essential. Enhancing the coke-bottle effect and optimizing airflow to the diffuser remains an area where significant time can be gained on modern F1 cars.

Drag

Aerodynamic drag is a critical force that affects Formula 1 car performance. It opposes the car's motion through the air and can significantly impact speed and lap times.

- Key Factors Influencing Drag

Body Shape: Streamlined designs minimize drag.

Frontal Area: Reducing the frontal area decreases drag.

Airflow Separation: Smooth airflow decreases turbulent drag.

- Strategies for Drag Reduction

Teams employ several strategies to reduce drag:

Streamlined Bodywork: Optimizing car shape to minimize turbulence.

Active Aero Elements: Real-time adjustments to optimize airflow.

Weight Reduction: Lighter cars experience less drag-induced deceleration.

Drag Reduction Systems (DRS): Allows momentary drag reduction on straights.

Impact on Speed

Balancing downforce and drag is crucial for top speed and lap times. The trade-off varies per circuit, affecting race strategies.

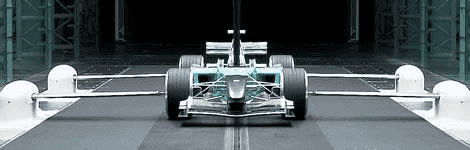

Wind Tunnel Testing

Wind tunnel testing has been a fundamental component of Formula 1 car development for decades. It's a critical tool for understanding how air flows around the car's body and its various aerodynamic components.

Wind tunnel testing involves placing a scale model of the car in a controlled wind tunnel environment. Air is forced over and around the model at varying speeds, simulating the conditions the full-scale car will experience on the track.

Key aspects of wind tunnel testing in Formula 1 include:

Simulating Track Conditions

Wind tunnels are equipped with advanced systems to simulate different track conditions. This includes adjusting the wind speed and direction to mimic specific circuits or driving scenarios.

Teams can fine-tune their cars for various tracks by replicating the exact conditions they expect to encounter during races. This helps in optimizing the car's setup and aerodynamic configuration for each race on the calendar.

Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) in F1

Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) is the sorcery behind Formula 1's aerodynamics. It's a digital wind tunnel, simulating how air flows around the car. Using complex mathematical equations, CFD predicts forces like drag and downforce. It's akin to having a crystal ball for aerodynamic performance.

Turning 0s and 1s into Victory: CFD isn't just lines of code; it's the difference between triumph and defeat. By fine-tuning a car's shape in the digital realm, teams maximize downforce and minimize drag. This digital dance with the wind translates to real-world victories and pole positions.

Some History of CFD in F1: Rise of the Digital Aerowarriors: CFD's roots in F1 trace back to the '80s. It began as a humble tool but evolved into the bedrock of design. Pioneers like Lotus led the way, and today, every team harnesses its computational prowess.

Examples of CFD in Action: Wings that Soar Digitally: Front wings sculpted to split airflow, rear wings generating that vital downforce, and diffusers creating low-pressure zones—each designed, refined, and validated through CFD. These digital designs manifest on the track, pushing cars to their limits.

Conclusion

Formula 1's aerodynamics play a pivotal role in unlocking speed and performance on the racetrack. Every aspect of a Formula 1 car's aerodynamics is meticulously engineered, from generating essential downforce to minimizing drag. Teams utilize advanced tools like wind tunnel testing and Computational Fluid Dynamics to achieve precision and innovation, finding the perfect balance between speed and stability.

As Formula 1 continues to evolve, so does the science of aerodynamics. With each passing season, new advancements are made, pushing the boundaries of what's possible. This ongoing pursuit results in even faster, more agile, and more exciting race cars, ultimately shaping the future of motorsport, one airflow at a time.